- Home

- Paul Fraser Collard

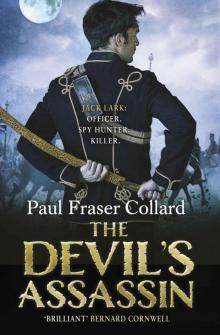

The Devil's Assassin (Jack Lark)

The Devil's Assassin (Jack Lark) Read online

Copyright © 2015 Paul Fraser Collard

The right of Paul Fraser Collard to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2015 by

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2015

All characters – other than the obvious historical figures – in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

Ebook conversion by Avon DataSet Ltd, Bidford-on-Avon, Warwickshire

eISBN: 978 1 4722 2270 1

Cover illustration © CollaborationJS

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.headline.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

About Paul Fraser Collard

Also By Paul Fraser Collard

Dedication

Praise

Glossary

Map – 19th Century Persia

Chapter One

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Epilogue

Historical Note

Acknowledgments

Read Jack Lark: Rogue, Out now

Paul’s love of military history started at an early age. A childhood spent watching films like Waterloo and Zulu whilst reading Sharpe, Flashman and the occasional Commando comic, gave him a desire to know more of the men who fought in the great wars of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. At school, Paul was determined to become an officer in the British Army and he succeeded in winning an Army Scholarship. However, Paul chose to give up his boyhood ambition and instead went into the finance industry. Paul still works in the City, and lives with his wife and three children in Kent.

By Paul Fraser Collard

The Scarlet Thief

The Maharajah’s General

The Devil’s Assassin

Jack Lark: Rogue (a digital short story)

To Dan, Mandy, Kayla and Harry

Praise for Paul Fraser Collard:

‘This is a fresh take on what could become a hackneyed subject, but in Fraser Collard’s hands is anything but’ Good Book Guide

‘Savage, courageous, and clever’ Good Reads

‘This is what good historical fiction should do – take the dry dusty facts from history books and tell the story of the men and women who lived through them – and Collard does this admirably’ www.Ourbookreviewsonline.blogspot.co.uk

‘This is the first book in years I have enjoyed that much that I had to go back and read it again immediately’ www.parmenionbooks.wordpress.com

‘Collard is to be congratulated for producing a confidant, rich and exciting novel that gave me all the ingredients I would want for a historical adventure of the highest order’ www.forwinternights.wordpress.com

bahadur hero, warrior

britzka long, spacious horse-drawn carriage with four wheels, with a folding top over the rear seat

charpoy camp bed, usually made of a wooden frame and knotted ropes

Chillianwala Battle of Chillianwala, 13 January 1849

chummery officers living together sharing living expenses

dacoit bandit/thief

daffadar native cavalry rank equivalent to sergeant

dakhbash Persian rank equivalent to corporal

dekho look (Hindi)

doli covered litter, sedan chair

firangi derogatory term for a European

fuadji Persian infantry battalion

ghats steps to a river

griffin nickname for an officer newly arrived in India

hookah instrument for smoking tobacco where the smoke is passed through a water basin before inhalation

Jack Sheppard infamous eighteenth-century thief

jawan slang for a native soldier serving in the East India Company

jewab answer

kick up a shine make a fuss

kot-daffadar native cavalry rank equivalent to troop sergeant major

kurta long shirt

mofussil country station or district away from the chief stations of the region, ‘up country’

munshi language teacher

pagdi turban, cloth or scarf wrapped around a hat

pankha-wala servant operating a large cooling fan

pannie London slang for burglary

picquet soldiers placed forward of a position to warn against an enemy advance

popakh conical hat made of ram’s wool worn by the Persian army

pagdi turban, cloth or scarf wrapped around a hat

sahib master, lord, sir

sarbaz regular Persian soldiers

serrefile line of supernumerary and non-commissioned officers placed in the rear of a squadron or troop of cavalry

shigram rural Indian carriage usually drawn by two bullocks

talwar curved native sword, similar to 1796 light cavalry sabre

Thuggee cult based on the worship of the goddess Kali

thug a member of the cult of Thuggee

tiffin light meal or snack served at lunchtime

vedette a mounted picquet

vekil Persian army rank equivalent to sergeant

The valley was the perfect place for an ambush. The rider scanned the steep sides with concern, his hard grey eyes roving over the heavy boulders that littered the slopes, wary in the face of the imagined danger. He saw the places where men

could hide, the positions where he would disperse his soldiers if he were not the one riding through the narrow, gloomy defile.

A small avalanche of stones caught his attention. Each fast-moving boulder kicked up a puff of dust, the thin, dry soil easily disturbed after so many months without rain. There was nothing to hold a man in his grave, the arid, friable surface reduced to so much sand.

The rider moved his hand carefully, unbuckling the holster on his right hip. He reached inside and wrapped his fingers around the hilt of his revolver, the metal hot to his touch. He felt the gun’s weight, its solidity reassuring. It was ready to fire, the five barrels loaded with care that morning, each one sealed with a thin layer of grease to prevent a misfire. The rider had learnt never to leave anything to chance. He could never be sure when the dacoits who roamed the high ground and preyed on the unwary and the unready would try to take the lone traveller who rode the barren lands. So he prepared for battle each day, priming his weapons and hardening his soul.

His eyes were never still as they roamed over the hidden crevices, his senses reaching out, searching for danger. He stopped his horse and listened. At first he heard nothing, the lonely quiet of the high ground pressing around him. He was thinking of slipping from the saddle and putting his ear to the ground to listen for movement when he heard the rumble. It sounded distant, like an early-morning express train far in the distance. His sable mount twitched its ears, sensing its master’s unease, its right foreleg pawing nervously at the soil as it was ordered to wait.

The rumble increased, the noise building steadily. The rider tightened his grip on the reins, shortening them and bunching them together so he could hold them in his left hand, his right clasped firmly around the hilt of his revolver.

He sensed movement to his left and tugged hard at the reins, pulling on the heavy metal bit forced into his horse’s mouth. He jabbed star-shaped spurs into the animal’s sides, forcing it into motion so quickly that its hooves scrabbled at the stony soil. As it lurched away, he saw the source of the movement. The heavy boulders kicked soil high into the air as they picked up speed and thundered down the sharp sides of the valley. They gathered momentum as they hurtled towards the solitary rider, careering down the slope, knocking other lesser stones from their precarious perch so that they created an avalanche that roared downwards in a wild melee of dust and stone.

The screams of the thugs echoed around the cramped confines of the valley as they unleashed their ambush. Ever since William Bentinck had taken over as governor of Bengal in 1830, the British authorities had brutally suppressed the followers of the cult of Thuggee. These worshippers of the goddess Kali had been the target of a concerted campaign to eradicate them, until only a few scattered bands remained, their brutal ritualistic killings a threat only to those foolish enough to travel the wild and lonely roads far from the influence of the British.

The rider reined his horse hard round, blinking away the dust that rolled over him. The inhuman shrieks of the ambush rang in his ears, drowning out even the heavy thump of his heart. The familiar icy rush of fear flushed through him before settling deep in his gut. There it twisted, churning his insides like a beast fighting to be freed, but imprisoned, held captive by the barriers he had constructed to contain it.

The first thug leapt over the fallen boulders, screaming like a banshee as he charged the rider, the naked steel of his talwar catching the sun as he flashed it overhead, readying the first blow.

The rider lifted his right hand. The fear was controlled, the bitter calm of experience overriding the terror of the ambush. The thug was close enough for the rider to see the animal snarl of hatred on the man’s face, the bared teeth as he howled his wild war cry, the bearded face beneath the stained pagdi twisted with rage.

The revolver coughed as the rider pulled the trigger. The bullet thudded into the thug’s face, smacking him backwards as if his feet had been pulled away sharply by an invisible rope. His corpse hit the ground like a rag doll, the contents of his skull spread wide, staining the dusty soil red.

The other ambushers did not hesitate. The rider had time to see the dirt on their faded robes, the tears and the rents in the worn fabric. The next face filled the simple sight on his revolver, the same visceral expression of hatred looming into view for no more than a single heartbeat before he pulled the trigger once more.

The man was punched to the ground, the revolver’s heavy bullet tearing through flesh and bone with ease. The second would-be killer crumpled, his pathetic, twisted corpse left lying no more than a yard away from the first.

The two remaining bandits rushed the rider. He got off a third, wild shot as they came close, but the deadly missile cracked past the ear of the nearest thug to score a thick sliver of stone from one of the boulders that had been meant to crush the rider into oblivion.

The rider gouged his spurs cruelly into his horse’s sides, forcing it to lurch forward. He rode at the surviving bandits, charging his enemy. They closed at a terrifying speed, coming together in a sudden blur of movement. The bandits had no time to slow their wild attack and the rider was past them before they could react. The treacherous ground gave way under their boots as they tried to turn to face him. One slipped, his curse the last sound he would ever utter.

The rider had forced his mount into a tight turn the moment he had burst through the pair of bandits. He let the still-smoking revolver fall from his hand and drew his sword. It was a fabulous weapon, the kind found in tales of valiant knights and beautiful damsels. Writing flowed down the length of the steel blade, the swirling script etched deep into the metal. The golden hilt wrapped snugly around the hand of the man wielding the sword, its dark red sharkskin grip mottled and stained from use.

It was the blade of a prince and it cut through the fallen bandit’s neck, slicing through the gristle to leave his head half severed, the blood darkening his filthy robes.

The last bandit threw his talwar across his body in a wild parry as the glorious sword whispered through the air, keening for his flesh. The rider twisted his wrist as he brought the weapon scything backwards, aiming the next blow even as the bandit attempted to recover from his first desperate parry, the fabulous sword moving quicker than the eye could follow.

The attacks followed swiftly, one after the other. The rider sat his horse as though the two were one single, monstrous beast, his skill instinctive. His pace never once faltered, forcing the last thug to scramble clumsily up the side of the valley in a desperate attempt to keep the steel from beating aside his defence.

The bandit screamed, his terror given voice as he slipped and fell, his notched and pitted talwar knocked from his hand by the relentless salvo of blows that came at him. The rider remained silent, even in the moment of victory. The thug scrabbled on the ground, trying to escape his fate. He had time to look once into the rider’s merciless eyes before the tip of the beautiful sword pierced his heart, the rider forced to lean far forward in the saddle as he drove the steel deep into his enemy’s flesh.

The rider twisted his sword, releasing the blade from the body of his fallen foe, then carefully manoeuvred his horse backwards, leaning from the saddle as he scanned the valley, looking for any threat that he had missed. A lone vulture met his gaze. The wizened old bird flapped its wings lazily as it landed on one of the boulders that had been meant to kill the white-faced rider. For a moment, man and bird stared at one another, the last two living creatures in the narrow valley contemplating the sudden arrival of death in such a remote place.

The rider slipped from the saddle. He wiped the sleeve of his coat across his face, smearing away the river of sweat that had run down to sting his eyes. The wool was heavy, the fabric poorly woven. The garment was not tailored to fit and it bunched uncomfortably over the rider’s shoulders. The red cloth showed the ravages of weeks in the saddle, but its pedigree was still recognisable. It was a uniform made famous the world over

by the men who sheltered beneath its folds. It was the red coat of a British soldier.

The rider retrieved his revolver, a wry grimace appearing on his lean face as he inspected the metal and saw the deep scratch that the impact with the stony soil had scored into its side. He paid no heed to the four corpses that littered the ground. He was long accustomed to death.

He walked quickly back to his horse, anxious to be away. He murmured quietly to calm the beast, the first sounds he had uttered since the four wandering thugs had launched their sudden ambush; then, with a single bound, he hurled himself into the saddle and turned his tired mount to face the path that had been partially blocked by the fallen boulders.

He let the horse pick its own way through the rubble, turning his back on the men who had sought his death, leaving them to the vulture and the other animals that would relish a feast of fresh flesh.

Another band of dacoits was no more.

He reached into the saddlebag that contained the ammunition for his revolver. He frowned as he saw how few cartridges were left. His days wandering the lonely paths were coming to an end. He would have to face a return to civilisation, to the people he had rejected for so long.

He gathered his horse’s reins in one hand and urged it to pick up the pace. It would take him many days to reach his destination, but he was in no hurry. He had not set out to be alone for so long, but still he did not feel the need to find company. The days had dragged into weeks, the weeks into months, but he would not rush to find the future as once he had.

He would let it find him.

Bombay, October 1856

The British officer was sprawled in the leather club armchair, a week old copy of the Times laid carelessly in his lap. Three bottles of Bass beer sat on the drum table beside him, their precious contents long gone. The officer slept fitfully, despite the effects of the food and drink he had consumed. He was not alone in the guests’ lounge. It was the time for rest, for slumbering through the hottest hours of the day, when all sensible fellows retired to the cool of the lounge or slunk away to their beds to await the fresher air of evening. The better echelons of Bombay society had only just returned to the city, and they slipped into a coma of indolence after tiffin, hibernating until evening arrived and the coaches came to collect them for a turn around the Esplanade or, for the more energetic, a drive to the splendour of the Malabar Hills or the harsh beauty of the black rocks at the Breach.

THE REBEL KILLER

THE REBEL KILLER The Lost Outlaw

The Lost Outlaw Jack Lark: Recruit (A Jack Lark Short Story)

Jack Lark: Recruit (A Jack Lark Short Story) The Devil's Assassin (Jack Lark)

The Devil's Assassin (Jack Lark) The Last Legionnaire

The Last Legionnaire The True Soldier: Jack Lark 6

The True Soldier: Jack Lark 6 Jack Lark: Redcoat (A Jack Lark Short Story)

Jack Lark: Redcoat (A Jack Lark Short Story) The Lone Warrior

The Lone Warrior Jack Lark: Rogue

Jack Lark: Rogue The Scarlet Thief

The Scarlet Thief